More than 11 years revealing secrets because there is no excuse for secrecy in God’s true religion – The Watchtower, June 1st 1997; Dan 2:47; Matt 10:26; Mark 4:22; Luke 12:2; Acts 4:19, 20.

Written and Published By: Miss Usato, Last Updated: February 6th, 2026

AvoidJW has this Supreme Court Hearing streaming Live on our Homepage. Below is a summary with quotes from the Translations of each day.

“Equal footing means that faiths have the right to be assessed under the same conditions. It cannot be understood as an unconditional obligation to provide support to all faiths and communities of faith.”

– Liv Inger Gjone Gabrielsen

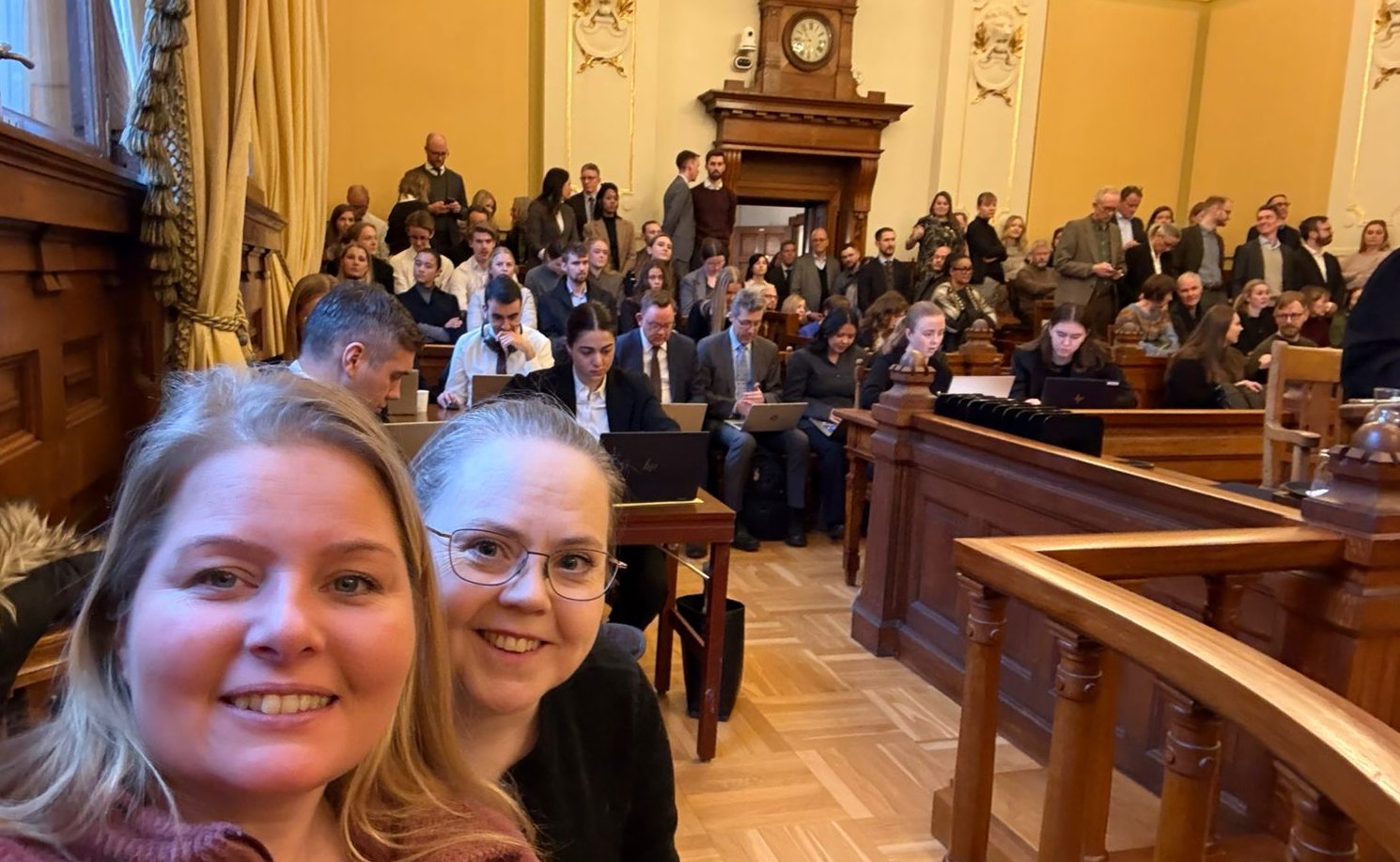

Supreme Court house, Norway – Day two will be the States Arguments for half of the day, then Watchtowers defense lawyer, Ryssdal for the next half. Reports from Former Jehovah’s Witnesses present say the line was out the door to get into the Supreme Court. Only 2-3 Former Jehovah’s Witnesses were able to get seats inside.

Day 2 of the Supreme Court hearing continued with a focus on where religious freedom ends and state-granted privilege begins.

As the State concluded its arguments in the Supreme Court on Day 2, the message was delivered with increasing clarity and force: freedom of religion in Norway is firmly protected, but it does not guarantee public funding, privileged legal status, or exemption from human-rights scrutiny.

From the outset, Liv anchored the State’s position in the Constitution itself. Section 16 establishes freedom of religion and affirms that all faiths and communities of faith shall be supported on an equal footing. But, she stressed, that language has a precise legal meaning.

“Equal footing means that faiths have the right to be assessed under the same conditions,” Liv said. “It cannot be understood as an unconditional obligation to provide support to all faiths and communities of faith.”

To underline this, the State pointed to the Storting’s own explanations when Section 16 was adopted. Parliament made it explicit that the provision was never intended to lock funding arrangements permanently in place.

“This provision shall neither entail new obligations for the state nor new rights for religious and philosophical communities or individuals,” Liv quoted from the preparatory works. The reference to support, she explained, reflected the existing financing system at the time, but “cannot reasonably be understood as establishing a constitutionally protected requirement that these arrangements remain unchanged in the future.”

In short, the Constitution guarantees equal assessment, not guaranteed funding.

“When Jehovah’s Witnesses are asked to explain their practice, they answer by referring to their own texts. Those texts describe exclusion as a loving arrangement and explain how members are expected to avoid those who leave.”- Liv Inger Gjone Gabrielsen

The State then addressed claims under Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which prohibits discrimination in the enjoyment of Convention rights.

Liv emphasized that Article 14 is not a free-standing right. It applies only where differential treatment lacks a legitimate purpose or is disproportionate.

“Even if there is no violation of Article 9, Article 14 can still be relevant,” she said. “But the differential treatment must be linked to a protected characteristic and must lack objective justification.”

That threshold, the State argued, is not met here. Jehovah’s Witnesses were given a reasonable opportunity to apply for both registration and grants under the new law. The criteria were written, publicly available, and developed through preparatory works. The application process followed ordinary administrative procedures.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses have had a reasonable opportunity to apply,” Liv said. “And the criteria have been applied in a non-discriminatory way.” The fact that Jehovah’s Witnesses were the first religious community to lose funding under the revised scheme does not, in itself, demonstrate discrimination.

“Being the first to be assessed under new criteria does not make the assessment arbitrary,” she added.

One of the most pointed rebuttals came in response to claims that the State had interpreted religious doctrine.

“The state has not taken a position on whether Jehovah’s Witnesses’ teachings are correct,” Liv said. “Nor on whether exclusion decisions are religiously valid.” What the State assessed was practice, not belief, and it relied heavily on Jehovah’s Witnesses’ own descriptions of that practice.

When authorities asked the organization to explain its exclusion and avoidance practices, Jehovah’s Witnesses responded by pointing to their own publications and website articles.

“When Jehovah’s Witnesses are asked to explain their practice, they answer by referring to their own texts,” Liv said. “Those texts describe exclusion as a loving arrangement and explain how members are expected to avoid those who leave.”

Those same materials, she noted, had also been submitted by Jehovah’s Witnesses themselves in earlier Norwegian court cases, including the 2022 Supreme Court judgment on exclusion. “The descriptions in the decisions are very close to Jehovah’s Witnesses’ own description of their practice,” she said. “They are factual and not hostile or derogatory, and they go no further than necessary.”

The State also addressed arguments related to weddings and registration, drawing on case law from Latvia.

Liv made clear that the ability to conduct a religious ceremony with civil-law effects is not a protected religious right under the Convention.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses can still conduct a religious wedding in the Kingdom Hall, with exactly the form of liturgy the religious community itself wants,” she said.

The only difference is that individual members must also register the marriage with civil authorities.

“A trip to City Hall does not interfere with religious freedom,” Liv added.

“Nothing emerged during the case processing that would have triggered a duty to re-investigate,” – Liv Inger Gjone Gabrielsen

Even if the court were to consider the decisions an interference, which the State does not concede, Liv emphasized that they sit at the very lowest end of what could qualify as intervention. “This is not a ban on religious practice. It is not an approval scheme,” she said. “Jehovah’s Witnesses remain a religious community no matter what.” There are no restrictions on belief, worship, or internal organization. The measures concern only access to public funding and administrative status.

At the same time, the State argued that the decisions pursue a legitimate aim: protecting the rights and freedoms of others, including the right to leave a religious community freely.

“When Convention rights come into tension, they must be weighed against each other,” Liv said. The State also stressed that it is not required to choose the most intrusive or most effective tool.

“The Convention does not require the state to select the best possible solution,” she noted. “It requires that the measures chosen are reasonable and pull in the same direction as other safeguards.”

Finally, the State addressed claims that the decisions were inadequately investigated or based on incorrect facts. Because the case is subject to full judicial review, Liv explained, alleged procedural errors have no independent significance. “Where the court has full review competence, any errors in the administrative process do not affect the validity of the decision,” she said.

The decisions were not based on isolated statements, but on a consistent picture of evidence that included Jehovah’s Witnesses’ own materials, supported by individual accounts. “Nothing emerged during the case processing that would have triggered a duty to re-investigate,” Liv concluded.

As the State closed its case, the overarching position was unmistakable: religious freedom in Norway is strong, equality is required, but public funding is conditional, and no religious community stands above the law when fundamental human rights are at stake.

“If the State intends to continue refusing,” Ryssdal added, “there will be many more millions in the years to come.”

– Watchtowers Lawyer, Ryssdal

Before we get into Ryssdals Arguments, I’d like you to try to count the lies, because many were expressed in his arguments. This is all recorded; these statements by Watchtower’s lawyer will be online forever.

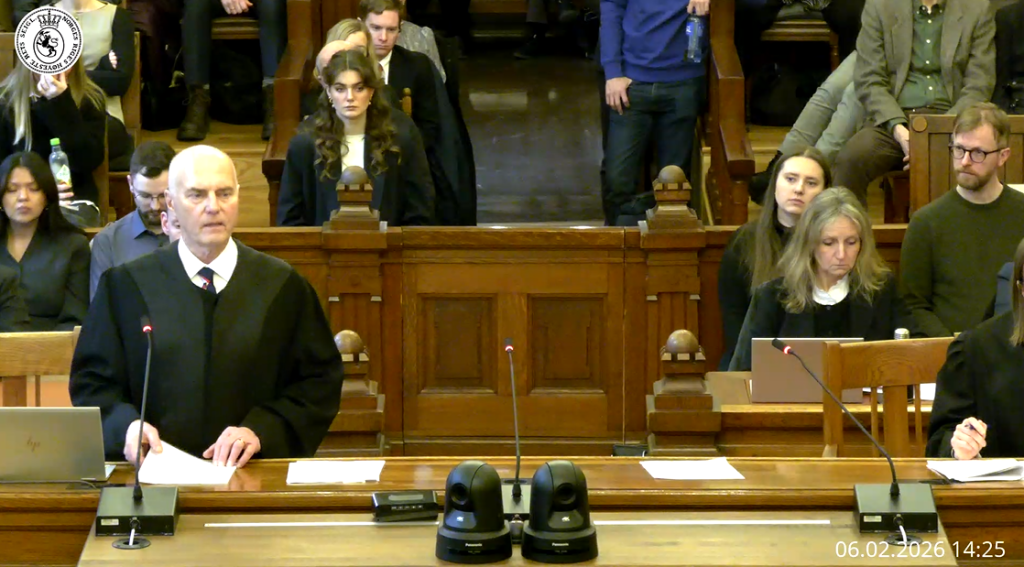

Ryssdal, Watchtowers’ lawyer, began his arguments around 11:30 A.M. in the Supreme Court. He starts by making it loud and clear that he rejected both the State’s framing of the case and its language. From the outset, he positioned the dispute squarely within European human rights law, insisting that Norwegian authorities had misunderstood what is protected under freedom of religion.

“This case has an important human rights dimension,” Ryssdal said. “Human rights imply that the last word lies with Strasbourg.” (Home to the European Parliament and Council of Europe). He argued that even if Norwegian courts find no violation under domestic law, the European Convention on Human Rights must take precedence, particularly when religious freedom is at stake.

Ryssdal identified what he described as clear interventions by the State. At the core, he said, were two decisions directed specifically at Jehovah’s Witnesses as an organization: the refusal of registration and the refusal of state grants.

“The first year alone was approximately 15 million kroner,” he said. “Over four years, we are cautiously talking about around 60 million kroner, probably more.” These measures, he argued, cannot be viewed in isolation. Taken together, they constitute a continuous interference with religious freedom. “If the State intends to continue refusing,” Ryssdal added, “there will be many more millions in the years to come.”

Ryssdal then moved directly into European Court of Human Rights case law, bypassing broader constitutional discussion.

“It can be useful to get an overview,” he said, “but I want to go directly to the judgments that relate to religion and to what is the topic of our case.” He relied heavily on cases involving religious minorities in Austria, Turkey, and Croatia, arguing that interference does not require a ban on religion.

“The State did not get away with saying that these communities were merely tolerated,” Ryssdal said, summarizing Strasbourg precedent. “That they were not banned, that they could meet freely, that was not enough.” What mattered, he argued, was denial of what the Court called “special privileges.”

“Special privileges will of course encompass financial transfers,” he said, “registration, as well as protection of the right to marriage and confidentiality.” In his view, once a state chooses to grant such privileges to religious communities generally, denying them to one group constitutes interference under Article 9.

“‘Shunning’ is not a concept Jehovah’s Witnesses accept,”

“Shunning was invented by Apostates”

– Watchtowers Lawyer, Ryssdal

A major portion of Ryssdal’s argument was devoted to language, specifically the State’s use of the term “shunning.” I realized while watching the live stream that Ryssdal paced back and forth every time he mentioned “Children” and “Shunning” in the same sentence.

“Shunning’ is not a concept Jehovah’s Witnesses accept,” Ryssdal said flatly. He objected not only to the word itself, but to what he described as its emotional weight. “We do not use that expression,” he said. “It does not have a good Norwegian translation.” Instead, Ryssdal urged the court to focus on the Bible’s wording, particularly the phrase “stop associating.”

“Even there,” he said, “‘limit association’ would be a more precise expression when time allows.” From a linguistic perspective, he argued, this does not mean cutting people off entirely. “It is not like Jehovah’s Witnesses turn away from people on the street,” Ryssdal said. “They have normal jobs, private lives, and ordinary social contact.” Which contradicts thousands of personal testimonies flowing in all corners of the world.

He then said that the word “shunning” was a word invented by apostates. Describing the practice as sweeping isolation, he insisted, is “far too strong a description of how Jehovah’s Witnesses function socially.”

Ryssdal acknowledged that the State had shifted toward using the term “social distancing”, but insisted this too must be understood carefully. “Social distancing simply means keeping a distance,” he said. “It does not imply active mistreatment.”

(JW publications: Watchtower, August 2018: “Loyal Christians will not maintain spiritual or social fellowship with those who have been disfellowshipped.” Watchtower Study Edition, October 2021: “We do not greet a disfellowshipped person, nor do we socialize with him.”)

He then noted that the term is used widely in other contexts. “You are told to keep a distance from an abuser,” Ryssdal said. “The expression is well understood.” He also pointed to foreign case law. “The Belgian Supreme Court used the term ‘passive social distancing,’” he said. “That is quite descriptive.” According to Ryssdal, this is not an active practice designed to punish others. “It is not something you do to torment people,” he said. “It is something you do to keep yourself in peace.”

Ryssdal insisted that what the State characterizes as social control is, in fact, religious discipline grounded in scripture. “The practice is clearly rooted in the Bible,” he said. “It is not something taken lightly.”

He cited 1 Corinthians 5:11, reading the passage that instructs believers to stop associating with members who engage in serious wrongdoing. According to Ryssdal, the purpose of this practice is not exclusion, but restoration. “The purpose is to help the sinner himself,” he said. “This is a religion that allows for return.” He referenced Hebrews 12:11 to reinforce the point: “Correction is painful in the moment, but it yields a fruit that leads to peace.”

“There is a low threshold for withdrawal,” he told the court, stressing that members are free to leave at any time and that consequences are neither intended nor imposed by the religious community. He even cited a personal testimony from JW’s stating, “I could leave anytime I want.” “I never felt any pressure or fear.” According to Ryssdal, the idea that fear of exclusion plays any role in decision-making is largely imaginary.

“If you are in Jehovah’s Witnesses, you are normally satisfied with it,” he said. “If you are not satisfied, all you do is say you are out and get out.” He rejected the suggestion that members live with anxiety about discipline or expulsion.

“No one goes around really worrying about whether they are going to be excluded,” he said, adding that exclusion is not something people think about unless “something else” is going on.

“This is not a system of surveillance or police activity.”

“Throwing out a minor, it does not exist in our faith.”

– Watchtowers Lawyer, Ryssdal

One of Ryssdal’s strongest assertions was that Jehovah’s Witnesses do not monitor or investigate members’ lives. As if judicial committees and such were just “friendly reminders.”

“This is not a system of surveillance or police activity,” he said. He rejected the idea that biblical guidance functions as enforceable behavioral rules. “All religious scriptures contain guidelines and requests,” Ryssdal argued. “They cannot be read as legally binding behavioral descriptions.” Responsibility, he said, lies with the individual believer. “This is a personal relationship between the member and his or her God.”

(Yet: Elder Manual (Shepherd the Flock of God): “Elders should investigate allegations of wrongdoing.” “A judicial committee should be formed to determine repentance.)

Ryssdal again returned to the issue of what the State calls social isolation or shunning, repeating that this is not an organizationally enforced practice.

“This is rooted in the biblical command,” he said, referring again to Corinthians. “But it is a matter of personal conscience.” He acknowledged that many believers will choose to limit contact with former members. “Many will think,” he said, “that they do not want to have anything to do with someone who used to be part of the community.” But he insisted this is not an obligation and is not enforced by the organization.

“It is not a legal call,” Ryssdal said. “It is not enforced. It is a personal decision.” He also denied that the doctrine supports cutting off family members. “It is not support for not having contact with former family,” he claimed, even while acknowledging that individuals may still choose distance.

Ryssdal argued that the possibility of exclusion plays no meaningful role in how members think about their faith.

“Being excluded does not seem to be part of the assessment at all,” he said. In his telling, this explains why young people can make what he called “important choices” calmly and without fear, because exclusion is simply not something they consider.

When the discussion turned to minors, Ryssdal was unequivocal. He stated that he was not aware of any minors being excluded in recent years and went further, describing such a scenario as fundamentally incompatible with Jehovah’s Witnesses’ beliefs.

“It is completely unbiblical,” he said. “Unthinkable for us.” Referring to situations where children might be expelled from the home or cut off due to religious discipline, Ryssdal dismissed the idea outright.

“Throwing out a minor, it does not exist in our faith,” he told the court. He stressed that even in situations involving illness, family crisis, or conflict, continued contact is not only permitted but expected.

“It may be necessary to have contact,” he said, pointing to family responsibility as overriding any other consideration.

Ryssdal closed this part of his argument by rejecting the notion that children raised as Jehovah’s Witnesses live under constant threat of discipline or expulsion.

“They do not walk around in a permanent fear of being thrown out and excluded,” he said. According to him, the very idea misunderstands the internal culture of the faith.

“The practice of Jehovah’s Witnesses is completely unbiblical to act in that way.”

“Family ties are not broken. That is also a biblical obligation for Jehovah’s Witnesses.” – Watchtowers Lawyer, Ryssdal

Addressing one of the most sensitive issues in the case, Anders Ryssdal insisted that exclusion from Jehovah’s Witnesses does not sever family relationships.

At this point in Ryssdal’s argument, the bench intervened. One of the judges began questioning how Ryssdal’s description of continued family bonds aligns with what happens in practice when someone leaves Jehovah’s Witnesses. The judge asked directly about family relationships, particularly where exclusion intersects with close relatives.

Ryssdal responded by insisting that family obligations remain intact: “Family ties are not broken. That is also a biblical obligation for Jehovah’s Witnesses.” He emphasized that care for family members is not optional, even when someone is excluded. “Jehovah’s Witnesses are taught to take care of their family for the rest of their lives,” he said, adding that this applies equally to elderly parents, children, and close relatives.

The judge then pressed further, sounding exasperated, raising scenarios discussed earlier in the case: “What happens when the excluded person is no longer part of the household?” Ryssdal acknowledged the distinction. “Yes,” he said, “that would typically be an adult.”

He argued that the legal and practical responsibility changes once a person is no longer a dependent, but insisted this does not amount to abandonment. “If an adult leaves Jehovah’s Witnesses, it is a different situation than when you are responsible for another person.” He argued that Jehovah’s Witnesses are explicitly taught to maintain responsibility for family members, regardless of religious status. “We love our siblings, parents, and children and continue to be a family,” he said.

Ryssdal acknowledged that leaving the religious community can involve formal steps, such as submitting a written resignation, but rejected the idea that this leads to enforced family rupture. Where contact changes, he argued, “it reflects individual choice rather than organizational command.”

To support this position, Ryssdal pointed to academic material submitted to the court, including international comparative research. In one cited analysis, the authors note that religious communities often balance two competing principles: preserving internal cohesion while keeping the exit door formally open.

As summarized in the material before the court, Protestant religious associations, including Jehovah’s Witnesses, are described as protecting their teachings “from erosion” while still making it relatively easy for members to leave. According to that research, there are “no national or international indications that it is difficult to leave Jehovah’s Witnesses.”

Ryssdal emphasized that this conclusion aligns with testimony already heard by the court, including statements from state witnesses. The unresolved question, however, is not whether one can leave, but what happens afterward.

Ryssdal acknowledged that two principles operate simultaneously within Jehovah’s Witnesses’ doctrine: “no national or international indications that it is difficult to leave Jehovah’s Witnesses,” guidance to limit association with those who leave the faith, equally strong teachings requiring family bonds to remain intact.

He maintained that these principles coexist, and that family relationships are not overridden by exclusion.

(Yet: Watchtower, April 2013: “Family members who are not part of the household should avoid unnecessary association.” + Former-member testimony: “I wasn’t cut off officially. I was just… no longer invited. No calls. No holidays. No emergencies unless unavoidable.”)

I look at this photo and see all of these Jehovah’s Witnesses, piled up to attend today’s Hearing. Listening to Ryssdal repeatedly insisting that leaving Jehovah’s Witnesses is straightforward, pressure-free, and largely uneventful, a claim he returned to several times in different forms. Do they pretend they don’t know? Are they second-guessing the supposed one true religion? Do they see the holes in the stories, the lies?

Ryssdal stood in court and said, “No one worries about being excluded,” and that “family ties are not broken.” That statement alone tells survivors everything they need to know. If shunning “doesn’t exist,” then why have thousands of former members independently described the same loss of parents, siblings, and children? Denial isn’t evidence. It’s a strategy. Ryssdal will continue his argument (lies) on Monday, February 9th, 2026.

Elders’ Book: Download a Copy in your language

JW Publication: Keep Yourselves in God’s Love

JW Publication: What Can the Bible Teach Us?

Furuli’s Website: My Beloved Religion

VARTLAND February 5th, 2026: Dissenters come from far and wide to follow the Jehovah’s Witnesses case

VARTLAND February 5th, 2026: Dissenters come from far and wide to follow the Jehovah’s Witnesses case

Office of the Attorney General, representing the State of Norway

Glittertind AS Law Firm representing Jehovah’s Witnesses

Reporter

Translator

Analysis